pledge() and unveil() in SerenityOS

This post describes the implementation and use of pledge() and unveil() in SerenityOS.

SerenityOS is proud to be the second operating system to adopt the excellent pledge() and unveil() mechanisms from the OpenBSD project.

If you’re not familiar, let me introduce them:

pledge(): “I promise I will only do X, Y and Z”

Most programs have a pretty good idea of what they’ll be doing in their lifetime. They’ll open some files, read some inputs, generate some outputs. Maybe they’ll connect to a server over the Internet to download something. Maybe they’ll write something to disk.

pledge() allows programs to declare up front what they’ll be doing. Functionality is divided into a reasonably small number of “promises” that can be combined. Each promise is basically a subset of the kernel’s syscalls.

Once you’ve pledged a set of promises, you can’t add more promises, only remove ones you’ve already made.

If a program then attempts to do something that it said it wouldn’t be doing, the kernel immediately terminates the program.

The prototype looks like this:

int pledge(const char* promises, const char* execpromises);

The two arguments are space-separated lists of strings. promises take effect right away, and execpromises take effect if/when the process uses exec().

Here’s an example from the /bin/cat program in SerenityOS:

int main(int argc, char** argv)

{

if (pledge("stdio rpath", nullptr) < 0) {

perror("pledge");

return 1;

}

...

As you can see, the very first thing cat does is inform the kernel that we’re only gonna be doing stdio and rpath stuff from now on. Pretty simple!

So what are the different promises we can make? Here’s the current list from the SerenityOS manual page for pledge(2):

stdio |

Basic I/O, memory allocation, information about self, various non-destructive syscalls |

thread |

The POSIX threading API |

id |

Ability to change UID/GID |

tty |

TTY related functionality |

proc |

Process and scheduling related functionality |

exec |

The exec(2) syscall |

unix |

UNIX local domain sockets |

inet |

IPv4 domain sockets |

accept |

May use accept(2) to accept incoming socket connections on already listening sockets. It also allows getsockopt(2) with SOL_SOCKET and SO_PEERCRED on local sockets |

rpath |

“Read” filesystem access |

wpath |

“Write” filesystem access |

cpath |

“Create” filesystem access |

dpath |

Creating new device files |

chown |

Changing file owner/group |

fattr |

Changing file attributes/permissions |

shared_buffer |

Shared memory buffers |

chroot |

The chroot(2) syscall |

video |

May use ioctl(2) and mmap(2) on framebuffer video devices |

Inside the kernel, each process stores its current set of promises in Process::m_promises. Most of the action happens in the Process class. When a syscall is invoked, we check that the calling process has made the right promises before proceeding. This is usually done by the REQUIRE_PROMISE(promise) macro:

int Process::sys$setuid(uid_t uid)

{

REQUIRE_PROMISE(id);

...

The macro expands to some code that verifies that the current process has either made no promises (pledge() is opt-in) or has made some promise(s) and id is one of them. If there are promises but no id, the program is immediately terminated by an uncatchable SIGABRT.

Sometimes, things get a bit more complicated. For example, to accommodate the windowing system, we make an exception to allow getsockopt() with SO_PEERCRED on local sockets for processes that have pledged accept:

int Process::sys$getsockopt(const Syscall::SC_getsockopt_params* params)

{

...

if (has_promised(Pledge::accept) && socket.is_local() && level == SOL_SOCKET && option == SO_PEERCRED) {

// We make an exception for SOL_SOCKET::SO_PEERCRED on local sockets if you've pledged "accept"

} else {

REQUIRE_PROMISE_FOR_SOCKET_DOMAIN(socket.domain());

}

...

We’ll be tweaking these promises as we learn more about how they fit into SerenityOS. The implementation currently feels quite invasive, and there are various improvements to make, so this is just a snapshot of how it works at the moment of writing.

unveil(): “I will only access paths X, Y and Z, so hide everything else.”

Now that we’ve limited ourselves to a small set of syscalls with pledge(), the next step is to limit our view of the file system. This is where unveil() comes in!

unveil() works very much like pledge(), except you pass in paths and permissions for those paths:

int unveil(const char* path, const char* permissions);

path can be either a file or a directory. If it’s a directory, the permissions will apply to any file in the subtree of that directory.

permissions is a string containing zero or more of these letters:

r: Read accessw: Write accessc: Create/remove accessx: Execute access

Just like pledge(), permissions can only be reduced, never increased.

Another important difference is that unlike pledge(), trying to open a file that’s not visible due to unveil() will not terminate the program. Instead, the attempt will simply fail with ENOENT (or EACCES if the path was unveiled, but not with the requested permissions.)

Let’s look at an example from our /bin/man program:

if (unveil("/usr/share/man", "r") < 0) {

perror("unveil");

return 1;

}

unveil(nullptr, nullptr);

This program knows up front that it will only be reading from files within the /usr/share/man subtree.

The second call to unveil() with null inputs tells the kernel that we’re done with unveil() and won’t need to specify any more paths. After this, it’s no longer possible to call unveil().

In the kernel, all the magic happens in path resolution (the VFS class.) The very first thing we do in VFS::resolve_path() is this:

KResultOr<NonnullRefPtr<Custody>> VFS::resolve_path(StringView path, Custody& base, RefPtr<Custody>* out_parent, int options, int symlink_recursion_level)

{

auto result = validate_path_against_process_veil(path, options);

if (result.is_error())

return result;

...

If a process has opted into using unveil(), there will be a list of paths and permissions in Process::m_unveiled_paths. We’ll check the path parameter against the list, and possibly short-circuit the path resolution with an ENOENT or EACCES if the path is not available.

Visibility from userspace

Promises for each process are visible in /proc/all. For a list of unveiled paths, you’ll have to look in /proc/PID/unveil. Since that’s a bit more sensitive, only the process owner and the superuser can see the paths.

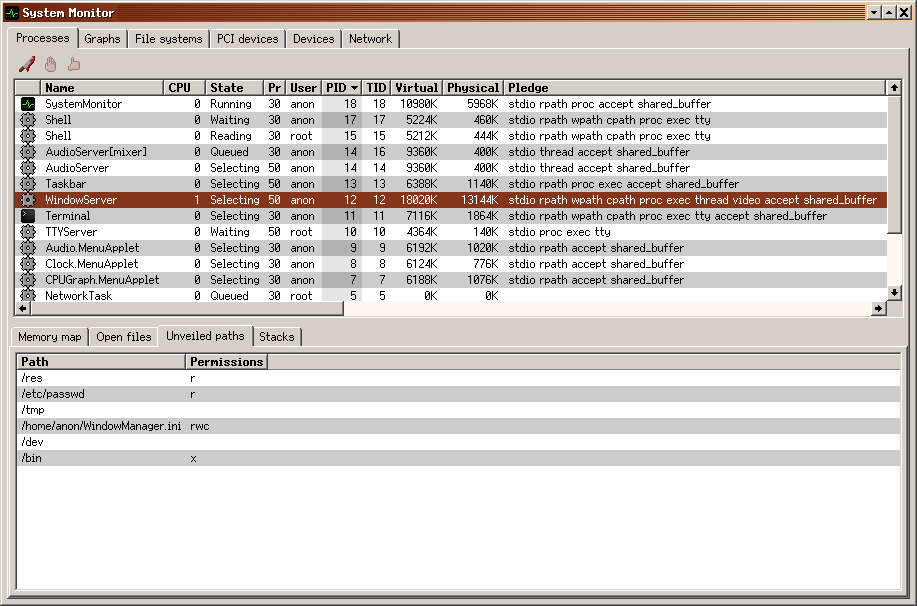

All of this information is visualized nicely in the SystemMonitor program:

In the screenshot above, you can see what each running program has pledged, and since WindowServer is currently selected, we have a list of its unveiled paths below. Pretty cool!

Some differences from OpenBSD

Since SerenityOS is a different system from OpenBSD and shares no code with it, it’s natural that the needs are a bit different. These are some of the differences we have at the moment:

No hard-coded paths in the kernel

OpenBSD hard-codes paths to various things and relaxes restrictions to certain paths based on pledges. I’ve been trying to avoid that so far, since it feels strange for the kernel to assume things about filesystem layout.

Separate promise for threading

It seemed unnecessary to allow any program to gain concurrency by default. I’ve added the thread promise for this purpose. On OpenBSD, all you need for threading is stdio.

Separate promise for accept()

We have a bunch of programs that set up a listening socket at startup. Since those programs don’t need to create any more sockets, or make any outbound connections, it’s good to be able to drop the unix and/or inet promises after setting up the listener.

I’ve added the accept promise for this purpose. On OpenBSD, this would require unix and/or inet depending on the socket type.

In closing

I believe pledge() and unveil() are excellent mitigation mechanisms, and I’m really happy to start using them throughout all of the programs that make up SerenityOS. Huge props to Theo de Raadt and the OpenBSD team for coming up with the ideas.

The implementations in SerenityOS are still young and immature, just like the rest of the system. We’re continuously improving on things as we go. If you’re interested in this sort of thing, you’re more than welcome to help out!

Also, if you’d like to see how these things were implemented, I recorded both hacking sessions and posted them to my YouTube channel:

Thank you for stopping by! Until next time :^)